| Головна » Статті » Поезія » Езра Паунд |

Кун пройшов за династичний храм і увійшов в кедровий гай, і далі вийшов до річкової заплави, і з ним Ю-цзи, І Тян скупий на слово, і "нас не знають,"- мовив Кун,- "Ти будеш управляти колісницею? Чи це тебе прославить, чи слід мені зайнятись колісницею або стріляти з лука? Чи повправлятися в публічних виступах?" Й Цзи-лу сказав: "Я б зміцнював укріплення." Й Хуей сказав: "Якби я управляв провінцією, То б встановив порядок кращий, аніж зараз." І Чай сказав: "Я обираю маленький храм у горах з дотриманням обрядів і виконанням відповідних ритуалів," І Тян сказав, торкаючись рукою струн своєї лютні, Лунали тихі звуки, коли він руку прибирав зі струн, і звуки здіймалися, як дим, над листям, й він пильнував за звуками: "Ось місце для купання, І хлопчики стрибають з дошки, або сидять у зарослях і грають на мандолінах." І посміхався Кун однаково до всіх. Цзен-цзи хотів дізнатися: "Хто відповів найкраще?" І Кун сказав: "Вони всі говорили правильно, Це означає, кожен відповідно своїй природі." І замахнувся Кун своїм кийком на Юань Янга, Був Юань Янг за нього старшим, Бо Юань Янг сидів обіч дороги, удаючи, що він вбирає мудрість. І Кун сказав: "Ти старий дурень, отямся, Встань і зроби хоч щось корисне." І Кун сказав: "Шануйте схильності дитини З миті, коли вона вдихнула свіже повітря, Та п'ятдесятирічний чоловік, не знаючий нічого, не вартий шани." І "Якщо принц збирає біля себе усіх учених і митців, не будуть змарновані його багатства." І Кун сказав і записав на листі фікуса: "Якщо людина не здатна дати собі лад, Вона не може управляти іншими; І якщо чоловік не здатен дати собі лад, Його родина не буде виконувати його розпорядження; І якщо принц не здатен дати собі лад, Він не зуміє навести лад у своїх володіннях. Й Кун називав слова "лад" і "шанувати брата" Й нічого не казав про "життя після смерті." І він сказав: "Впадати в крайнощі уміє кожен, Легко стріляти мимо цілі, Важко влучати точно в центр."

І вони сказали: "Якщо вчинив убивство чоловік, чи мусить батько його обороняти і переховувати?" І Кун сказав: "Він мусить його сховати."

І Кун віддав свою доньку Кон-Чану, Хоча Кон-Чан був у в'язниці. І він віддав свою племінницю Нан-Юну, Хоча Нан-Юн не мав посади. І Кун сказав: "Ван правив розсудливо, У його дні держава процвітала, І навіть я згадати можу час, коли історики лишали пустими сторінки у своїх записах, Я маю на увазі події, про які вони не знали, Але, здається, такий час минає." І Кун сказав: "Без характеру ти будеш Не здатен грати на цьому інструменті Або виконувати музику придатну для співу. Несе цвіт абрикосу Вітер зі сходу на захід, Й я намагався уберегти його від опадання." Конфуцій (27/08/551 до н.э. — 479 до н.э) - справжнє ім'я Кун-цю (Кьюнг Чіу), але в літературі частіше вживається Кун-цзи (цзи - учитель), рідше Кун Фу-цзи, что означает Шановний Учитель Кун Персики і абрикоси - китайська метафора учителя і учнів

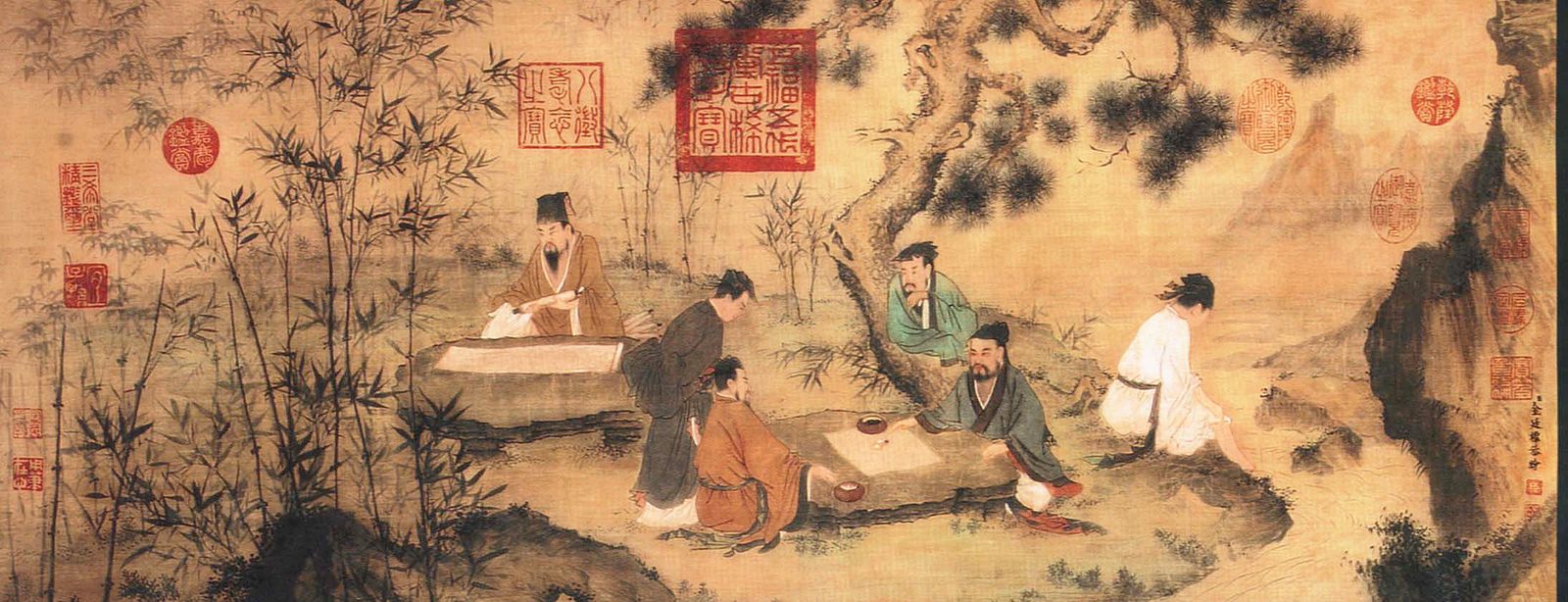

Канто ХІІІ - В якості вступного слова Це Канто демонструє уявлення Паунда про відмінності між Конфуцієм і Заходом в галузях освіти, філософії, релігії, мистецтва і моралі. Він неявно протиставляє орієновану на суспільство філософію Конфуція, , етику і політику його практично грецьким сучасникам Сократу і Платону, які дискутували про абстрактні відмінності і "космологічні прозріння". Пізніше Паунд виділив би Арістотеля як західний еквівалент Куна, оскільки Арістотель єдиний серед греків мислив з позицій реальної політики, а не ідеальних республік. Арістотель написав або підштовхнув до написання положень конституцій у 158 грецьких державах. Паунд порівнює релігійні положення конфуціанства і християнства, підкреслюючи орієнтацію Куна на земне життя: Кун прагнув виховати у своїх учнях почуття єдності через виконання ритуалів та відповідальність за життя, яке служить суспільству, в якому вони живуть, а не за їхнє особисте спасіння після смерті. Паунд розцінював християнську заповідь "любити ближнього свого" як неявний дозвіл втручатися в приватні справи іншої людини. Він пропонує нам конфуціанську концепцію "шанувати брата", яка поважає приватну сферу, як корективу християнської цінності. Нарешті Пвунд протиставляє Куна, творця педагогіки його часу, системі, запровадженій в німецькій практиці, стимулюючій здобування знань задля знань, а не як підготовку до життя. Паунд вважав, що такі знання не мають значення при вирішенні життєво важливих проблем і шкодять окремим людям, оскільки спрямування знань від учителя до учнів включає їх в єдину систему, перетворюючи на потенційних рабів тиранії. У "Провінціалізм ворог" (ч.ІІ), 1917, Паунд поставив Куна в один ряд з Флобером і Генрі Джеймсом, борцями з прихованим поневоленням, викликаним "вдовблюванням учнів як деталей частини механізму і [...} звиканням чоловіків до відчуття себе частинами механізму для якогось застосування: на противагу тому, щоб спочатку подивитися, як їх будуть використовувати" ("Провінційність, ч.ІІ, 233-34). Навпаки, як видно з центральної сцени Канто, взятої з "Аналектів, 11:25", стосунки Куна з учнями направлені на те, щоб з'ясувати, що вони знають про себе, і зосередити увагу на тому, що найважливіше для їхнього майбутнього. Він не вказує їм, що думати, а лише задає відповідні запитання - учні пропонують відповіді, які не цензуруються і не співставляються з нормами правильності. Важливо зазначити, що Кун відмічає переваги і оцінює відповіді кожного з учнів в "Аналектах, 11:25", але Паунд пропускає місця, в яких той так робить. Таким чином, Канто - це не поєднання перекладів, призначене для пояснення тексту Конфуція, а швидше те, що Мері Патерсон Чейдл назвала "солянка з уривків, елегантно з'єднаних разом", обумовлена власними ідеями Паунда про значення і масштаби конфуціанства та уроки, які воно може запропонувати західній культурі. Це проявляється у відмінностях між Канто і його джерелом, миттєвими але дуже значущими способами, якими Паунд відступається від нього, щоб викласти свою позицію. Це оригінальне бачення Паунда, в якому мало або нічого спільного з традиційним розумінням конфуціанського вчення. Єдиним джерелом для цього Канто є французький переклад «Чотири китайських класика» Г. М. Патьє під назвою «Доктрина Конфуція», який містить «Le Ta Hio» («La Grande Étude»), Tchong Young («Invariabilité dans le milieu»), Лунь Юй («Entretiens Philosophiques" ["Філософські розмови" або "Аналекти") та Мен-Цеу ("Mencius "). Центральний епізод Канто (розмова з учнями) виведений з «Entretiens Philosophiques"11:25 в перекладі Патьє. Новіші видання «Аналектів» (Lau, Eno, Chin) розділили 11:2 на дві частини, так що 11:25 стало 11:26. У своєму "Mr. Villerant’s Morning Outburst» Паунд опублікував прозовий переклад цього епізоду в Короткому ревю у листопаді 1918 р. ([V], P&P III: 221-223), який подається у глоси та може бути знайдений у Джерелах.

РОМАНІЗАЦІЯ ІМЕН КИТАЙЦІВ Паунд послідував за романізованими іменами та китайськими термінами, наданими його джерелами (Cheadle 7), тоді як новіші дослідження як конфуціанських робіт, так і перекладів Паунда слідували за системою піньїна (Cheadle, Lan, Chin). Таким чином, проект Кантос буде дотримуватися практики включення китайського слова спочатку у використовуваній Паундом романізації, а потім у піньїні в квадратних дужках. Для канто XIII Паунд використовує французьку романізацію, яку він знайшов у своєму джерелі: "Доктрина Конфуція: Les Quatre livres de philosophie morale et politque de la Chine". Traduite par M. G. Pauthier. Париж 1814. Pdf. Інформація про учнів Конфуція взята з "Додатка" Аннпін Чин та коментарів до її перекладу "Аналекти" (Пінгвін 2014) та онлайн-перекладу Роберта Ено.

Canto 13 Kung walked by the dynastic temple and into the cedar grove, and then out by the lower river, And with him Khieu Tchi and Tian the low speaking And "we are unknown," said Kung, "You will take up charioteering? "Then you will become known, "Or perhaps I should take up charioterring, or archery? "Or the practice of public speaking?" And Tseu-lou said, "I would put the defences in order," And Khieu said, "If I were lord of a province "I would put it in better order than this is." And Tchi said, "I would prefer a small mountain temple, "With order in the observances, with a suitable performance of the ritual," And Tian said, with his hand on the strings of his lute The low sounds continuing after his hand left the strings, And the sound went up like smoke, under the leaves, And he looked after the sound: "The old swimming hole, "And the boys flopping off the planks, "Or sitting in the underbrush playing mandolins." And Kung smiled upon all of them equally. And Thseng-sie desired to know: "Which had answered correctly?" And Kung said, "They have all answered correctly, "That is to say, each in his nature." And Kung raised his cane against Yuan Jang, Yuan Jang being his elder, For Yuan Jang sat by the roadside pretending to be receiving wisdom. And Kung said "You old fool, come out of it, "Get up and do something useful." And Kung said "Respect a child's faculties "From the moment it inhales the clear air, "But a man of fifty who knows nothng Is worthy of no respect." And "When the prince has gathered about him "All the savants and artists, his riches will be fully employed." And Kung said, and wrote on the bo leaves: If a man have not order within him He can not spread order about him; And if a man have not order within him His family will not act with due order; And if the prince have not order within him He can not put order in his dominions. And Kung gave the words "order" and "brotherly deference" And said nothing of the "life after death." And he said "Anyone can run to excesses, "It is easy to shoot past the mark, "It is hard to stand firm in the middle."

And they said: If a man commit murder Should his father protect him, and hide him? And Kung said: He should hide him.

And Kung gave his daughter to Kong-Tchang Although Kong-Tchang was in prison. And he gave his niece to Nan-Young although Nan-Young was out of office. And Kung said "Wan ruled with moderation, "In his day the State was well kept, "And even I can remember "A day when the historians left blanks in their writings, "I mean, for things they didn't know, "But that time seems to be passing. A day when the historians left blanks in their writings, But that time seems to be passing." And Kung said, "Without character you will "be unable to play on that instrument "Or to execute the music fit for the Odes. "The blossoms of the apricot "blow from the east to the west, "And I have tried to keep them from falling."

CANTO XIII - BY WAY OF INTRODUCTION https://www.thecantosproject.ed.ac.uk/index.php/a-draft-of-xvi-cantos-overview/canto-xiii?showall=1&limitstart=

The canto presents the ways Pound situates Confucius in relation to the West along the axes of education, philosophy, religion, arts and morals. He implicitly contrasts Kung’s philosophy, oriented toward society, ethics and politics, to that of his Greek near-contemporaries, Socrates and Plato, whose discussions handled abstract distinctions and “cosmological guesses” (GK 97). Later, Pound would single out Aristotle as Kung’s Western equivalent, since Aristotle had been the only one of the Greeks to think in terms of real politics, not ideal republics: “Aristotle compiled or caused to be compiled descriptions of the constitutions of 158 Greek states” (GK 341). From a religious point of view, Pound compares Confucianism to Christianity, emphasizing Kung’s orientation towards the life on this earth: Confucius aimed to cultivate in his disciples a sense of community through the performance of rituals and a responsibility for a life of service to the society they live in, not their individual salvation after death. Pound saw the Christian maxim of "love thy neighbour" as an implicit permission to intrude in another person's private affairs. He invites us to consider the Confucian concept of "brotherly deference," which respects the private sphere, as a corrective to the Christian value. Finally, Pound opposes Kung as educator to the pedagogy of his own day, a system inspired by German practice, designed to pursue knowledge for its own sake, not as a preparation for life. Pound felt this knowledge was irrelevant to vital questions and damaging to individuals, since by directing knowledge solely from teacher to students, it subjected the latter to a uniform system, turning them into potential slaves to a tyranny. In “Provincialism, the Enemy II” (1917), Pound aligned Kung with Flaubert and Henry James against unseen, customary enslavement brought about by “hammering the student into a piece of mechanism for the accretion of details, and [...] habituating men to consider themselves as bits of mechanism for one use or another: in contrast to considering first what use they are in being” (Provincialism; P&P II: 233-34). By contrast, as can be seen from the central scene of the canto taken from The Analects 11.25, Kung’s interaction with students is designed to draw out what they know about themselves and focused on what is most vital to their future. He does not tell them in advance what to think, but only asks a relevant question—the students come up with answers that are neither censored nor aligned to a standard of correctness. It is important to know that Kung does express preferences and judge each student’s answer in The Analects 11.25, but Pound cuts the passages where he does so. Thus, the canto is not a collage of translations designed to illuminate the Confucian text, or recover a “true” Confucius, but is rather what Mary Paterson Cheadle called a “pastiche of passages knit elegantly together,” governed by Pound’s own ideas about the meaning and scope of Confucianism and the lessons it has to offer to Western culture. These emerge in the distinctions between the canto and its source, the minute but highly significant ways in which Pound departs from it to present his position. This is Pound’s original point of view and has little or nothing to do with Confucian studies traditionally perceived. only source for this canto is the French translation of the Four Chinese Classics by G. M. Pauthier entitled Doctrine de Confucius, which contains Le Ta Hio (“La Grande Étude”), Tchong Young (“Invariabilité dans le milieu”), Lun Yu (“Entretiens Philosophiques” [“Philosophical Conversations” or Analects]), and Meng-Tseu (“Mencius”). The central episode of the canto (the conversation with the disciples) is taken out of Entretiens 11.25 in Pauthier’s translation. Newer editions of The Analects (Lau, Eno, Chin) split 11.2 into two parts, so that 11.25 has become 11.26. In his “Mr. Villerant’s Morning Outburst,” Pound published a prose translation of the episode in the Little Review in November 1918 ([V], P&P III: 221-223) which is given in the glosses and can be found in the Sources.

ROMANIZATION OF CHINESE NAMES Pound followed the romanization of names and Chinese terms provided by his sources (Cheadle 7), whereas newer research on both Confucian works and Pound’s translations has followed the pinyin system (Cheadle, Lan, Chin). The Cantos Project will therefore follow the practice of including the Chinese word first in the romanization Pound used, and then in pinyin, in square brackets. For canto XIII, Pound uses the French romanization which he found in his source: Doctrine de Confucius: Les Quatre livres de philosophie morale et politique de la Chine. Traduite par M. G. Pauthier. Paris 1814. Pdf. The information on Confucius’ disciples is taken from Annping Chin’s "Appendix" and commentaries to her translation of The Analects (Penguin 2014) and Robert Eno’s online translation of The Analects.

| |

| Переглядів: 224 | Рейтинг: 0.0/0 |

| Всього коментарів: 0 | |